A Bun For A Good Boy

Excerpts from the first chapter of an unpublished novel of The Crimean War, based on original letters sent to his wife by William Dawson of the 2nd Battalion Rifle brigade.

Some years ago, I received a phone call from an elderly lady wanting to know if I was interested in antique glass. Well in my shop we dealt with a great assortment of items including as it happened, antique glass. I drove over to see the collection, but decided it wasn’t old enough for the shop and declined the offer. As I was leaving, still on good terms with the owner of the glass, she said “Is there anything else that interests you?” I could have said any if the things we normally dealt in … ancient coins, medals, paintings, jewellery, small antiques … things that were far more likely to draw a response, but for some unknown reason I said “Letters from the Crimean War?”

It was an absurd thing to say and I cannot for the life of me imagine why I said anything as bizarre and as specific as that. I had never said it before, but it was almost as if she was expecting me to say those very words, for her face brightened and without saying a word or even moving, she opened the drawer beside her and handed me a small pile of letters. In more fanciful moments I feel it was though the letters and I were destined to find each other.

Some years later, I turned those letters into an (as yet) unpublished novel and as I’ve been up to my neck in family matters this past month and have failed miserably to produce a Substack, I’ve decided to leak a few (longish) excerpts from the opening chapter.

I have to say at this point that whenever reading his letters, I hear Billy Dawsons voice speaking to me and so whilst writing the novel, I tried very hard to keep this voice involved. His after all, is the voice of authority. He was there.

***************************************************************

A Bun For A Poor Boy.

No private soldier ever asks for war. You may think it likely that no sane man ever wants to heap death and destruction on any part of the world, no matter how small.

How can any man wish for the things I have seen in battle?

Screaming men, clawing at their sightless eyes. Horses, wide eyed in pain and panic as their insides flop out to be trodden into the mud. Men sliced in two, smiling gently in death.

But you can take it from me, officers want war all the time, for they all want promotion. There never was a junior officer that didn't want to be a General one day, and, if you cannot buy a Regiment, the best way for that is to be noticed in some action or other. I have known officers pray for war. They get down on their knees and pray to the Almighty for war and for tens of thousands of poor souls to meet their maker so they can be promoted and pay off their gambling debts. There are very few Lieutenants who would consider a hundred or so corpses rotting on some foreign plain a high price to pay for a Captaincy. There are very few Captains who would be upset by the destruction of a few hundred acres of crops or the massacre of a few dozen of his command if a Majority was at stake.

I may not know a lot, but I do know about officers.

There are, of course, good officers and bad officers, in the same way that there are good and bad men, but, strangely, the two are not necessarily the same thing. A bad man is not always a bad officer, and a good man can sometimes make a very poor officer. I have worked for any number of officers, both good and bad. I have cleaned for them, run about for them, turned a blind eye for them, even done their duties for them. I have learned to respect a good many of these gentlemen.

But I only ever liked one.

****************************************************************

Chapter One.

There are many ugly words indelibly connected with the Crimean War; "Alma", "Sebastopol", "Inkerman".

"Scutari" is another. Perhaps it is the most ugly. I have only to hear the word Scutari and a dull shudder goes down my spine for with it comes a thousand ghosts.

The hospital at Scutari was as ugly as the word. An ugly place, with ugly scenes and around every corner ugly disfigurement and death. The smell of the place alone, will remain with me for as long as I live.

The nights were long and sleepless with the sounds of death all around; the groans and whimperings of those poor men who chose to slide gratefully to their maker and the terrified screams of those who didn't want to go. The dank halls were full of the ghostly shimmering of lanterns reflected from the dripping walls. And, I would swear to it, the faint flickering of departing souls as they flew to wherever it is departing souls fly.

I often wonder how many hearts ended their monotonous drum beat in that huge, rat infested building. How many happy memories vanished among those dark slimy corridors. I had many hours in Scutari to contemplate life and death.

Scutari was all things. I came to think of it as the very end of civilization, for everywhere you looked were shattered limbs, excrement and pain. But for some it was undoubtedly a place of hope and safety, though I wonder how far across the Styx must a mind be to regard Scutari in those terms. It was certainly Miss Nightingale and the stench of death and cold running walls.

"We need beds Mr Dawson" she said to me. "Do you think you can make us some?"

Of course I could make beds. I could have made her four poster beds and decorated and fluted the posts fit for Queen Victoria. But Miss Nightingale simply wanted the men off the floor which was a natural thing to want, for the floors of Scutari hospital were verminous and damp and as she said these words to me, human waste was running around our feet.

And so I made beds and I repaired the rotting beds that were there already and because of that I missed much of the cruel Crimean winter that carried off so many of my friends.

"We need you more than the army does", said Miss Nightingale, when I asked her if I could return to the war. "You can be a soldier another day, but today you are our carpenter"

Making beds was easy and somehow she had managed to procure good quality timber. Lord alone knows how. It was difficult enough buying a loaf of bread in the East at that time and I'd have said finding timber of such quality was impossible, but she did it. She also found tools fit for purpose which was another miracle, but Miss Nightingale was a miracle worker and was as determined as any person I have ever met. I'm pretty sure she could find ice in a desert if she set her mind to it. And this was the key to her success. Nobody else could find anything during that extraordinary winter. There was no food, fuel, clothing or transport to be found anywhere, for the great contending armies had swallowed everything worth having. But somehow she found it all.

So I made good use of her wood and tools and made beds fit for soldiers in a hospital that was not. Despite the cold, I worked outside whenever I could. I vacated the evil smelling corridors and worked in the grounds. I burned the old rotten timber and it kept me from freezing on all but the coldest days and, while I was measuring, plaining, sanding, sawing or cutting joints, I tried to forget about the scenes in the hospital and my thoughts turned to other things. Naturally, I was worried about my family so far away but somehow London was too remote and too painful to consider so I kept my thoughts simple and wondered about the war and how the army were doing without me. I often found myself remembering the start of it all, just a year or so before, and wondering how so much awfulness could have happened in such a short time.

****************************************************************

By returning to London before the other wives, Alice and the children cleverly avoided the dreadful scenes that were to take place on our departure from Portsmouth on February 24h

Few people managed to sleep that night. It was cold and frost blanketed the cobblestones around the barracks. One or two little fires sprang up in the gutters as the women burned leaves, twigs and anything else they could find, in a desperate attempt to fend off the cold. I suppose there must have been both men and women there but it is the women i remember. They filled St Nicholas's Street, many of them wanting to speak to their sons, brothers and husbands one last time before we sailed.

Others were just contented to be breathing the same air as them for as long as possible.

Seldom can there have been a more pitiable, and yet a more strangely assorted group of women. There was a well-dressed mother openly crying into her handkerchief being comforted by a mivvy from the gutter that she would not normally been seen dead with. There was the well-groomed wife and sisters of a young officer, destined to die a heroic death at the gates of Sebastopol, crying tears that fell to the earth alongside those shed by a mother whose son had taken the shilling to avoid prison and who was to die a lonely and painful death in Scutari.

By the gates, the ancient grandmother of an overbearing Sergeant had her head cradled in the lap of a young sister of a fresh faced rifleman. And there by the wall, a mother who wept for her only son, was lying prostrate in the arms of a good hearted woman with no connections to the army at all, who had just come to see what all the fuss was about.

But in the main they shared a common grief, those women, and in the cold and stagnant darkness of Portsmouth, as each woman cried in their own grief, they also cried for each other. A low cloud of communal despair hung dark over the town and a high pitched moan of misery was heard throughout the city. They did not leave the surrounds of the barracks all night, but talked in a low and pathetic manner to their soldiers through the windows of the building, or just sat by the roadside and cried.

They were right, too. Right to be petrified for the safety of their men, for about half of those husbands, fathers, sons and brothers were never to set foot on British soil again.

Life, however, never comes to a complete halt and amongst the grieving women the inevitable whores wandered around trying to drum up a little last minute business, their banter contrasting strangely with the mournful sobs and whispering in the square.

Besides the whores, there were some women there who shed no tears. These were the women who were fortunate enough to win the lottery, held amongst the wives, to see who was to be allowed to travel to the Crimea with their husbands. Women with children were ineligible, but lots were drawn by the rest, from Sergeants wives down. The eventual winner from our company, after innumerable calls of cheating, unfair play and favouritism, was Mrs Jenness. The other Rifle Brigade wives that travelled with us were Mrs West, Mrs Colton, Mrs Stopley, Mrs Verender, Mrs Goodwin and Mrs Byrnie. They were all very happy at the time, excited even, and their laughter, as it echoed round the square, sounded loud and rather strange amidst the sobbing. However, they didn't think themselves so lucky later that year and none of them would have gone if they'd known what they were in for.

There was certainly an atmosphere of distress and foreboding surrounding Portsmouth barracks that night. It was the sort of night you read about in cheap novels, when distant dogs howl at the moon and pale ghosts silently drift in and around the headstones of the local cemetery.

In this way it was somehow dreadfully in keeping with the mood of the town that our Pay Sergeant, in a fit of despair, chose that night to end it all. Some said it was through regret at leaving his wife and children near destitute, but we were all doing that. Some said it was a drunken gesture of regret to some young woman or other.

But whatever it was, John Wager, a good soldier and a pleasant man, after spending the day drinking at some Portsmouth Tavern, took himself round to the back of Southsea Castle. After making himself comfortable on the common, he brought out his razor, had a long lingering swig from a bottle of cheap brandy, and, in front of several horrified witnesses, cut his throat. Some weeks later when we were far away, we heard that his wife, in a fit of misery, poisoned herself. We never will know what went on between the two of them. There were rumours at the time that she had been unfaithful to him and had eventually crumpled under the guilt she felt after his suicide. There was, as I have mentioned, a lot of guilt at that time.

Guilt was the favourite subject of the Reverent Taylor, who used to read the sermon at St Georges when I was a child. I don't know why he felt so strongly about the subject but he used to tell us guilt was a burden that was carried by every man. "Some" he would say, "are strong, and do not notice its weight, whilst others are weak and succumb. But no matter who we are, no matter what our station in life, rich or poor, guilt affects all men. But let him return unto the Lord and He will comfort him"

I was never quite sure about the effects of guilt amongst my contemporaries. I used to look around me in church, and half the kids I knew would have stolen the halfpennies from the eyes of their dead grandmothers and not shown the slightest twinge of remorse. Guilt was not a common emotion in the back streets of Southwark when I was a boy. However, at the time of our departure for Turkey, guilt was affecting me greatly. To some degree, I could lessen this guilt by earning a little extra money that I could send home. I did this by taking on extra duties and working for an officer as a servant.

I had, ever since the birth of Lizzie, worked for a number of officers of the second battalion. I worked hard on their behalf and they had always seemed very pleased with me. In Canada, I had once been a servant to Mr Newberry, the paymaster. He was a very straightforward sort of gentleman, not the sort of man to recommend anyone for no good reason, and I took it as a compliment to my work that he unhesitatingly recommended my services to a young officer of a good family who had recently joined the Regiment. I had, of course, not known Mr. Malcolm for more than a week or so at that time but my first impression was he seemed a pleasant enough young gentleman. Not given to rages, drunkenness or bouts of melancholy or any of the other moods or vices that make life uncomfortable for a servant, so I was quite pleased with my new appointment.

Charlie was very much amused when he first saw Mr Malcolm, and said he didn't so much need a servant as a nursemaid, for my new Master was just eighteen years of age and didn't yet shave. But whatever his age, ability or temper, my family needed the money, and that was that as far as I was concerned

Mr Malcolm had given me orders to call him early in the morning we were due to sail. He was staying at the Portland Hotel, where many officers resided when we were in Portsmouth as it was a very comfortable lodgings and almost opposite the main entrance to the Clarence Barracks.

Unfortunately the sight of me, all ready to march, as I appeared at the barrack gates sent a ripple of panic through the crowd of women and led to a renewal of the wailing that had broken out every few minutes during the night.

"Oh God in Heaven, they're leaving now!" cried one poor old woman and started to rush towards the gates, presumably in the hopes of seeing her boy for one last time before he was sent out to face the Russian guns. Her boots slipped on the frosty cobblestones as she tried to push past me and I instinctively caught her before she had time to fall.

Helping her to her feet, I said, "Don't worry Mother, you'll know when we are about to leave! They'd never send the Rifles off without a fanfare or two now would they!"

I had thought she might welcome a few kind words and I might be helping to lighten the tension a little but, as I was speaking, her eyes narrowed to slits and she shrugged away my helping hand.

"Don't you worry?" She spat my own phrase back at me and glared as if it was my fault her son was going off to war. "You and your bloody Rifles! What'll you tell me when my Harry comes home in a wooden box? I expect you'll tell me not to worry then."

"Your Harry won't come home in a box! We'll all be home in a few months anyway!" I said reassuringly, "And he's a good, sensible sort of boy isn't he?"

In truth, I hadn't any idea who her Harry was, there being several Harry's in my company alone. Fortunately for me, she burst into tears at this point and was shepherded away by a younger woman who, for no reason I could imagine, also glared in my direction as if I'd hit the old girl.

A pretty young woman with dark eyes and long golden curls plucked my arm, and asked if I knew Billy B. I said I did and she thrust a letter into my hand.

"Give this to him" she said. "I don't suppose I'll get to speak to him this morning. I expect he's busy."

"I expect he's been getting himself pretty for the parade" I said. I knew Billy B and I knew his reputation for the ladies. I suspected there were at least half a dozen women outside the barracks crying into the handkerchief for the love of Billy B.

"Yes, that'll be him" she said. She smiled weakly as if she knew she was chasing a lost cause, and I doing likewise, pocketed her letter.

Another woman, with bright red lips and powdered face stopped me as I pushed my way through the throng.

"Where you off to Dearie?" she said, and latched onto my arm. "How about one for the road?"

"Sorry love" I said as I tried to free myself from her grip. "I'm in a bit of a rush, and besides," I added with a wink, "I'm a married man"

"Oh 'ark at 'Im," she said loudly to a group of her friends nearby "Ee's a married man!"

They all hooted with derision, and one of them shouted back, "She shouldn't have left you all alone then darlin'!"

I was having difficulty prising her fingers away from my arm and she pulled herself closer to me and said in a more confidential tone.

"Being married don't make no odds dear. I'm a married woman but I don't charge any more, either way. Just think, you got all that experience for no extra charge and I only live just round the corner."

"Look" I said, as I finally manage to free my arm, "Like I said, I'm in a bit of a hurry. We're off soon." And lamely, I added "I have to fetch my young officer from his hotel."

"Oh Blimey," she said, "I like 'em young. You couldn't fetch one for me too could you?"

She shrieked with laughter but could see I wasn't interested, and so, patting me on the cheek and still laughing raucously, she sauntered off in the direction of her friends.

As I watched her go, I nearly tripped over the prostrate form of a woman who appeared to have fainted in the gutter and was being revived by an earnest young vicar who, for some reason, was trying to revive her by holding her hand and reciting the 91" psalm, but I didn't linger and, seeing my way was reasonably clear, sprinted the last fifty yards and thankfully entered the expensive warmth of The Portland Hotel.

Mr. Malcolm was already awake and fully dressed when I arrived.

He looked tired and pale in the early morning light as if he'd not had much sleep. Whether this was from nerves or excitement I could not tell, but I could certainly tell he was embarrassed, for his mother was in his room, having decided at the last minute to stay in the town in order to be nearby until it was time for us to go. Like mothers everywhere, she was fussing over her son's appearance and checking with him that everything was packed

I hoped to heaven she didn't start asking awkward questions, as I had spent much of the previous day packing and repacking his trunks with the vast array of items needed by a young officer far from home and didn't want to start a search at this late hour.

"Yes Mother," he was saying as I entered the room. "I am quite certain I have everything I need. Indeed, I fear I have far too much. Father seems to think we shall be home before long."

"My dear," she said. "You can never tell with this sort of thing. I am quite sure your Uncle Willy said just the same before going off to the Peninsular'

"Uncle Willy was home nine months to the day after setting sail. He told me so himself."

"Yes, he returned home before the end of hostilities after having a leg shot off!" said his Mother with a certain amount of exasperation. "If it were not for that he would have found himself acutely short of underwear I am certain!"

"Although," replied Mr Malcolm, with a hint of a smile, "after losing his leg he might have found he had rather too many socks"

His mother glared briefly before smiling and visibly relaxing.

"Mother," Mr Malcolm continued. "Dawson packed yesterday. I am quite sure he didn't forget the underwear"

She looked at me and raised an eyebrow. I could have taken this either as a question or as a slur on my capabilities, but I decided to take it as a question, and replied,

"No Madam, Mr Dawson has plenty of underwear, I saw to it myself."

"Both winter and summer?"

"Yes, Madam," I said, "Underwear for all seasons"

At this, Mr Malcolm, who had been growing increasingly agitated, stepped in.

"Now Mother," he said, "I'm sure you don't want to spend the rest of the time we have left discussing my underwear"

She sighed loudly.

"No you are quite right." After a brief pause, she added, "I'm sure Dawson could be prevailed upon to fetch you some breakfast. I shan't have any myself, though I should welcome some tea."

I had been hoping Mr Malcolm would have some breakfast, as I'd heard they served some very fine bacon at The Portland and thought, if he didn't manage to eat his share, then I could certainly find a home for it myself. But I was to be disappointed.

"No!" he said quickly. "No breakfast". Then, after a moment's hesitation, "Tea? Perhaps I could manage some tea..."

Then, possibly feeling there was a need for an explanation, he added, "It's a little early in the morning for me"

There was no need, of course. An officer seldom needs to explain his actions to a private soldier but he was, as I have said, still very young.

He was also very pale and I still wasn't quite sure how much of that was nerves and how much was excitement, for the poor lad had never been far from his mother before and had certainly never left home to go to war.

They both managed several cups of tea and a large pile of toast and Mrs Malcolm continued to fuss over her son whilst I sorted out his belongings. Most of his baggage was already at the dock awaiting shipment but there was still one small trunk which he had with him in the hotel and which he needed on the voyage east. I packed it carefully and then repacked it after finding various essential pieces of equipment he had replaced in a drawer.

I arranged for the removal of the breakfast things, gratefully slipped the remaining piece of toast into my pocket, and was much relieved to see Mrs Malcolm return to her room so I could finish my duties in peace. A wagon for the officer's boxes was already outside the hotel and while we waited for his trunk's removal, Mr Malcolm sat on it in silence. He was staring out of the window into the street below. I was just giving the room one last search when, without looking up, he suddenly spoke to me.

"Do you think there will be much fighting," he said.

We both knew it was unusual for an officer to ask advice of a manof my rank, whatever the disparity in their ages, and I thought for a moment or two before answering. There had been a certain amount of debate in the barracks over just this point and opinion was split fairly evenly. About half took the line the Russians would sue for peace and we'd all be home before summer, the other half thinking war with such a vast enemy was folly and there was going to be an almighty fight.

Even Charlie, usually an optimist in the face of insurmountable problems, had said to me in a moment of reflection. "If Napoleon couldn't get to Moscow what chance have we?"

I didn't think it was likely we would have to march to Moscow from Constantinople, or wherever it was we were off to, but I wasn't too sure of my geography, so simply pointed out to Charlie, that if anyone could do it, The Rifle Brigade could.

I decided it wouldn't do anybody any favours if I scared the boy with rumours of imminent conflict and annihilation, and so thought it best if I tried to reassure him a little.

"Well sir," I said, somewhat hesitatingly. "Most of the lads think the Russians have no stomach for a fight and we'll be home in a few months."

He looked at me with broad distaste.

"I hope to God we're not," he said. "I told my father I'd be Lieutenant by the end of the year!"

Which just goes to prove, as my friend Charlie had said to me just the day before, "Whatever his age, an officer, is still an officer."

Portsmouth had been preparing for our departure for weeks.

Throughout the town posters were exhorting its inhabitants to give us a fitting send off and to accompany the "Gallant Rifles" to the station and Dock Yard. And so, when the time came for us to go, there was such a large crowd gathered that it was only with a certain amount of difficulty the women at the barrack gates could be forced back enough for the gates to be fully opened.

The crowd was simply massive. I wouldn't be surprised if you told me that every single inhabitant of the town was there. It was unfortunate the departure time was given on the poster as seven in the morning when the bulk of the regiment were not due to leave till eight. But, as luck would have it, my company and one other, had been given orders to leave early for the station for we were to take the train down to Southampton and embark onboard a ship from there.

At seven precisely, when I, together with a mere few hundred men, marched out of the gate to the accompaniment of the band of the 35th Regiment we were greeted by the deafening cheers of tens of thousands of excited townspeople. The streets were lined with men, women, and children from every mansion, every house and every tenement in the city.

I think even the inhabitants of the workhouse had been allowed out to wave and cheer us. Flags were waved, flowers were thrown and kisses were blown at us from every direction. During the magnificent pandemonium of the first part of that march, I threw off the shackles of guilt for a while and marched feeling as tall and as proud as I have ever felt in my life.

Strange to say, however, in the wealthier parts of the town we marched in near silence. It wasn't that the streets were any less crowded, but the emotions of the people who lived there were obviously a lot more restrained. They waved their handkerchiefs, dabbed their eyes and quivered their lips in an entirely refined manner in keeping with their social position. Nevertheless, I'm sure their good wishes and fond farewells were just as heartfelt.

We marched to the railway station where quickly we boarded a train heading west.

An hour later, the remaining companies, altogether over 800 strong, were to march to the dockyard to the strains of "Auld Lang Syne" and "The Standard Bearer". By this time even people from the outlying villages were swelling the crowds. There were over 10,000 people on the Common Hard alone and many more along the High Street and Ordnance Row. At the Dock gates there was a danger of the crowd losing all control and the Rifles had to fight their way through a mass of cheering men and women. One or two of our men were actually lost in the crowd for several minutes, but were fortunately returned by a host of friendly hands.

I am told that on their arrival at the jetty, the scenes of parting between husbands and distraught wives were terrible. The poor women who'd made it that far had been forced to run from the barracks to the dockyard behind the marching troops. By the time they arrived, some of them, having had to fight their way through the cheering crowd, had worked themselves up in to a state of hysteria. Several others, quite exhausted through lack of sleep and emotion, fainted on the frosty cobblestones and were in danger of being trampled upon Many others just stood and watched their men board the ship, with tears streaming down their frozen cheeks. The men were herded onto the ship, some cheering and waving to the massive crowd who were still shouting their messages of good luck and waving their flags, whilst others were desperately trying to get one last look at their women or were shouting one last message of affection.

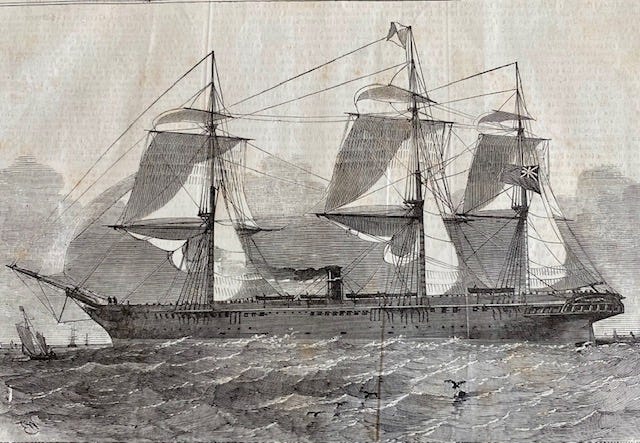

Eventually, as the troopship Vulcan set sail, her decks were awash with soldiers franticly waving to the crowd and to the women who had endured so much to catch this brief final glimpse of the men they loved.

In contrast, the women, having given their all in getting so far, stood in silent forlorn little groups, simply too cold and too tired to wave, without even the strength to continue their tears as silently, they watched the ship edge into the open sea.

But we only heard this. We did not see it with our eyes, as by then we had clattered our way down to Southampton. By and large we had travelled in silence, all still affected to some degree by the emotions of the departure, the crowds, the noise and the tears.

We were still unnaturally quiet when we reached Southampton, so disconsolately we shuffled from the train, silently said farewell to our homeland and stepped onto a floating palace.

**********************************************************************************************************

Please let me know what you think whether you liked it or not!

Hopefully next month this Substack will be back to normal.